We speak with the driving force behind one of Chicago’s first modern craft breweries — and of course there’s Star Trek quotes

Compared to breweries like, say, Weihenstephaner, ten years in business may not be a big hurdle to cross. But for Chicago’s Metropolitan Brewing, it is a major milestone not just for them, but for the city’s brewing scene as a whole.When Tracy Hurst and Doug Hurst got Metropolitan off the ground and sold their first beer in January 2009, they were at the vanguard of a Chicago craft brewing scene set to explode — and one that now boasts nearly 200 breweries a decade later. Back then inside city limits it was them, Goose Island, Piece, Rock Bottom … and that’s about it.

What’s it like being the first production brewery to open in about a decade in a city like Chicago? What’s it like fighting the pay-to-play and making noise in a world that doesn’t know what the hell to make out of a ragtag bunch of misfits making lagers in a garage on Ravenswood Avenue?

We spoke to Tracy Hurst — aka “craft beer’s obsequious minion” — about all this and more, plus what the next ten years might look like.

Guys Drinking Beer: I only really know of the Tracy Hurst and Doug Hurst that are “the people that run Metropolitan Brewing.” So back in 2008, what did what were you guys doing up until the point when said, “Okay, let’s open a brewery now.”

Tracy Hurst: I was running a photo studio of my own and working as a professional performer. So basically I was running two sole proprietorships. Doug was attending Siebel, and working in corporate audio / video production. So, you know, like putting together projects for big huge presentations at McCormick and things like that.

And the whole time I’ve known him he’s been brewing beer and he attended Siebel … he came back from Germany and started working on a business plan. So it took us a year to write the business plan and we set up our LLC in April of 2007. So from that point on, it was just pretty much all brewery all the time at that point.

GDB: So a little under two years to go from a plan to where you guys get to start brewing.

TH: April 2007 is when Metropolitan Brewing was born. Summer of 2008 is when we built out Ravenswood and our first brew was in December of 2008.

GDB: So talk to me about your memories of what opening a brewery in 2008 was like. Richard Daley is still the mayor, and when people say Chicago beer, they still think Old Style. Goose Island is still roughly three years away from the AB sale. What does all of that look like in retrospect?

TH: It was very much under the radar. Like, no one really knew exactly what we were doing. No one really understood … I mean, the Illinois Liquor Control Commission (ILCC) officer who came to the brewery to do an inspection had really no idea what he was looking at.

It was actually just really kind of quiet and under the radar, and people didn’t really know what was going on. The water department came by and asked about what we were doing, did a bunch of tests and pulled samples from our drains and things like that to test what we were doing to the water table.

And later, I got a letter basically saying “thank you for doing business in Chicago.” Because the brewery was so clean and we were so conscious of that kind of thing. So it was very much “cottage,” very much as if we had a 4500 square foot garage, basically.

In terms of setting up our culture to be friendly, and to be … what’s a better word for incestuous?

Tracy Hurst

And now breweries launch and they open a tap room, and there’s big parties and stuff — [on] our launch date we had three accounts and we just drove to each account. I remember Hopleaf was one, I can’t remember the other two anymore. They’re both probably gone. Actually — one was a pizza place in Wrigleyville that I know is gone. And we just…went to each place and had a beer and posted on social media.

And that was about it. It was much less fanfare, much less noisy.

GDB: Do you think it was more of a blessing or a curse, in terms of having that open runway to create your brewery from scratch? You guys more or less made up the rules.

TH: Well, it was a blessing in that we followed the rules that we knew, and that we could — in terms of the culture itself, that was more important.

I was actually just reminiscing — and I haven’t mentioned this to anyone else, actually — that there was a time where [Revolution founder] Josh Deth and [Half Acre founder] Gabe Magliaro and Doug and I all met at Hopleaf one night for beers and just talked about what we wanted to do and what we wanted it to look like.

And I’ll never forget it because [Hopleaf owner] Michael [Roper] walked by and said something like, really flattering. He said something like, “Wow, I’m seeing the Chicago beer industry right here at one table” or something like that.

[Ed. note — We reached out to Michael Roper to see if there was any chance he had any recollections of this conversation. We’ll update here as needed.]

And so in terms of setting up our culture to be friendly, and to be … what’s a better word for incestuous? Like, where people can get into the industry and move around in the industry?

GDB: Flexible, maybe?

TH: Collaborative! Yeah, collaborative. It’s a word we beat the shit out of but you know, it’s collaborative where if you want a certain job in brewing and you know, the breweries all talk to each other, and everybody talks to each other.

So it’s like, you can navigate your career the way you want within a relatively friendly industry. And that was kind of important. I thought it was important that we were setting up an industry that was inviting; that gave people a chance to try and do the things that they want to do — and to help each other out.

And there’s the there’s the cons of it — there are no self help or tech help manuals. There are no instructions that come with your brewing equipment. You kind of just have to learn on the fly. You have to learn how to fix stuff, which is hard because it’s frustrating and it’s scary but it’s cool because with each problem you solve, with each thing you fix you get more confident about what you’re doing, and you get better at your job.

And that is something after 10 years — I look around at my team and these are all seasoned individuals now. These are all experts, they’ve been in beer for longer than 10 years, most of them.

GDB: You just touched on something that I was curious about — I went back and I looked for anything I could find in terms of online media from ‘09 about your opening and there’s just nothing. The only thing I could find from around then was where you gave a comment to Crains on like they did like a story on pay to play…

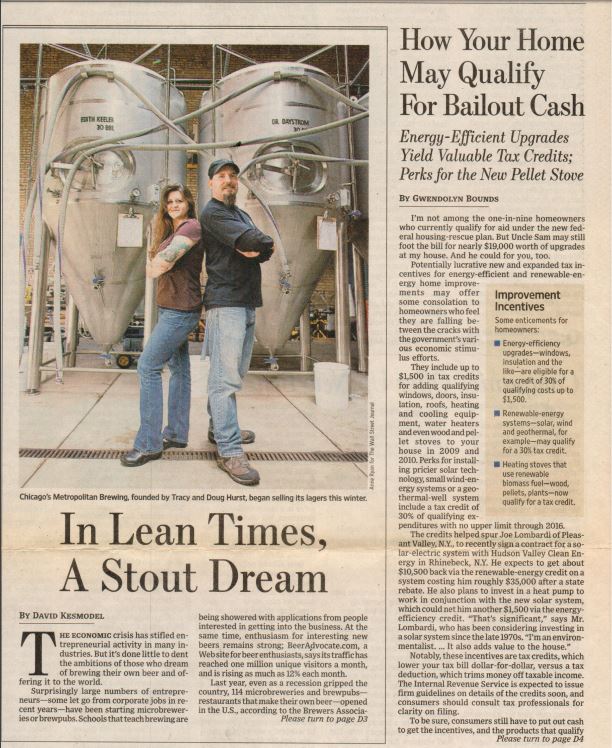

TH: Yeah, that was in ‘09. There was a little bit. We were in the Trib and we were in the Reader – Gabe was on the cover. I have some of those older articles if you want to see them [Ed. note: Tracy kindly scanned and sent, which you see in this piece] but yeah but there’s not a lot.

We were in the Wall Street Journal, in terms of craft beer being a cottage industry. The only reason I know about those articles is ’cause I clipped them. I don’t even know if we were scanning stuff online ten years ago.

GDB: The whole thrust of that Crains piece was about distributors and pay to play, all that. I you know you’re out there every day, selling beer — is the market any better now versus ten years ago?

TH: Yeah, it’s gotten better… It’s still bad.

I mean, the macros and people still throw money around and still break the rules and do pay-to-play but it has gotten a lot better. And I would say it’s not gotten better because the ILCC came down and cracked down on anyone — it got better because of the hustle of the people who sell craft beer in this industry in our in our area. In Chicagoland.

Because you know Windy City [the craft-beer focused distributor founded by the Ebels of Two Brothers Brewing and sold to Reyes in 2012], our distributor and other sales reps are out there explaining every. fucking. day that it’s not right to take pay-to-play — that everyone should have a shot based on the merits of their beer. That’s why it’s changed.

So now you have publicans and you have owners who won’t do pay-to-play. Who won’t even bother asking, let alone take advantage of it if it’s offered to them. That’s something I’m really proud of and I’m glad you mentioned that. That’s just purely Chicagoans doing the right thing.

Cmdr William Riker

“Best to just set some parameters and let it float.”

GDB: Talk to me about the process of just finding the space that you guys opened in Ravenswood. Did you go into it just like, “we need space to put a bunch of stainless and that’s it” or did you kind of have like any sort of idea that your space would just kind of become ground zero for everything that followed?

TH: We knew how to build a brewery because that that information is out there. You know, you can learn that from Siebel and you can learn that from reading books and going to breweries and stuff, talking to people. So I mean, any kind of infrastructure and stuff like that — we had a business plan.

So, you know, we knew what kind of barrel minimums we would need to sell — not make, that’s another thing. You can make beer all the live-long day, what counts is how much you sell. So we knew how much we needed to sell in order to make numbers that worked out our financials.

So, I mean, we went in with the backbone of a straight up manufacturing-style business plan. In terms of what kinds of beers we would make, an image, that was all laid out too. Metropolitan, the lagers, the engines and power theme — that was all laid down.

I believe in … okay so this is a long story:

There’s an episode of Star Trek, The Next Generation where there’s a mirrored group of people to the main cast. They’re young, they’re cadets, it’s called Lower Decks. And it’s sort of a story between the two groups of people, the main characters, and the the cadets that are sort of their mirror image when they’re younger.

Riker is working with someone at the conn, and she’s firing at a probe that they shoot out into space. She aims at it, she locks it in, she fires, she misses. She takes another shot, and she gets it. And Riker says, “Best to just set some parameters and let it float.”

And that’s what I’ve been thinking about. I mean, I should actually pull that down off of Amazon and make sure I get that quote right.

But the idea is: we knew we want to make German style beer. We knew we wanted to remain independent. We knew we wanted to grow organically rather than playing games with money. And then within those parameters, we kind of just … saw what happened.

Flywheel and Dynamo were first two beers and then Krankshaft hit the market in 2010. It immediately took the top seller spot, so okay — that’s our flagship then. You know, we thought Flywheel would be. But Krankshaft wound up being our flagship, so cool. I mean it still fits all within our parameters, but we just kind of waited to see.

So I’m more traditional in terms of small business where you don’t hit the market just doing what everybody else is doing. You look for a void to fill and then it’s your job to explain to people why what you’re doing is so great.

GDB: I am also curious about the decision to always and forever be a lager brewery — was that decision was based out of the love for that style of beer? Or was it the thought process of, in 2008 or 2009, knowing that “that’s what Americans are drinking, they’re drinking these lager beers and that’s what we need to sell in order to survive.”

TH: Right. You look at craft beer and [lager] was what was missing. And of course, doing our research, we found out that there are very good reasons why it wasn’t a thing. It’s harder to make, it takes longer, it’s more expensive, you know, all those details. But to us, those are all things that we could turn into strength.

And the fact that Doug is such a skilled brewer — even then was such a skilled brewer. To us, it felt like, “what the hell, we’re taking a risk — let’s risk it and really go for it and really do something cool and do something that we can talk about.” And then on the flip side of that, you’re also partly right — not so much in that that’s how American beer drinkers drink, but that’s how the world drinks.

Globally, nine out of ten beers consumed is a pilsner. And that’s not just the macros throwing off the numbers. Across China and Northern Europe, Scandinavia — I just recently learned that Dortmunder Export is a very popular beer in Sweden. I had no idea. So it seemed like a risk in terms of American craft beer. But in terms of how humanity drinks, making a pilsner is actually a pretty solid choice.

We knew we would have to wait it out or it may not happen — we may just have to explain to people, you know, forever and ever. But it turns out that we were kind of right. That eventually everyone comes around to something that’s super crushable, that’s food friendly, family friendly and more and more people are trying their hands at lagers now.

GDB: Now that it’s been a decade, was there a moment at any time in the last 10 years where you felt like maybe you could just like take a breath and say, “Okay, I think this business is, is going to make it.”

TH: No. [laughs.] Nope! Failure is always an option.

No, we are always working really, really hard. There’s always things we want to do. we want to hire more people, we want to enter more markets —

GDB: Well, I mean, there’s, there’s a difference between working hard on a business that is growing and working and workin on a business that’s going to like shutter its doors if you miss a paycheck in the next quarter. Can you think of a time where you got to that point, maybe?

TH: I mean, we have come and gone from that point. I would say when once you’re profitable, and your cash flow is comfortable — that sounds kind of simple, but that’s when you’re actually like, super comfortable.

But that’s usually when in small business, you take another risk. So, you know, when we got comfortable, we added beers, and then we got comfortable and then we added people. Then we got comfortable and then we expanded our distribution and stuff like that.

So, I mean, in the simplest terms, when you’re paying your bills comfortably, and you’re profitable, you’re stable. Keep doing what you’re doing, and keep keeping an eye on the market and things like that. But like I said, at this point: we have always been, at that point and ready to make another jump.

Tracy Hurst

If we get to the point where we have like, three dozen employees and everyone is leading a good life? That’s fine. Let’s just keep doing that.

GDB: What do the next 10 years for Metropolitan look like? Is it more focusing on Illinois and Wisconsin? Or maybe branching out? Maybe it’s going global?

TH: We are definitely going to branch out to some new Midwestern markets this year. We were going to add Jet Stream to our package lineup but the government shutdown might affect our plans to do that. We’re going to build out this space for sure — we have room to make a lot more beer here than we are.

And honestly, this place [the Rockwell facility] is where we can reach what you were talking about earlier: our business plan’s theme. So like you don’t close, but your business can just operate at that level. And then you innovate in other ways. Because it’s important for small business to not get stagnant.

You have to keep your eye on what the market is doing. You have to keep an eye on the community. And for all of us, this brewery is our vehicle, for sure. We all love our jobs, we love what we do. It’s easy to stand behind what we do. But we’re engaged in the local community, we’re engaged in the river cleanup efforts, we’re engaged in the Chicago Brewseum buildup.

We like working with other small businesses like Metropolis Coffee, Kyoto Black [Coffee]… So we’ll continue to come up with new and fun things to do. But this is home for the foreseeable future. We don’t have any plans to ship out of the Midwest. Ever, really. We don’t see the point. The local focus isn’t going to change and we feel more comfortable keeping our beer close to home. Let’s just keep going and sharpen our skills in other ways related to what we do.

And honestly, if we get to the point where we have like, three dozen employees and everyone is leading a good life? That’s fine. Let’s just keep doing that.

We’ve edited this interview slightly for clarity and space. Tickets for Ten Years Lager remain on sale and you should strongly consider attending and celebrating a major milestone for one of Chicago’s most important breweries.